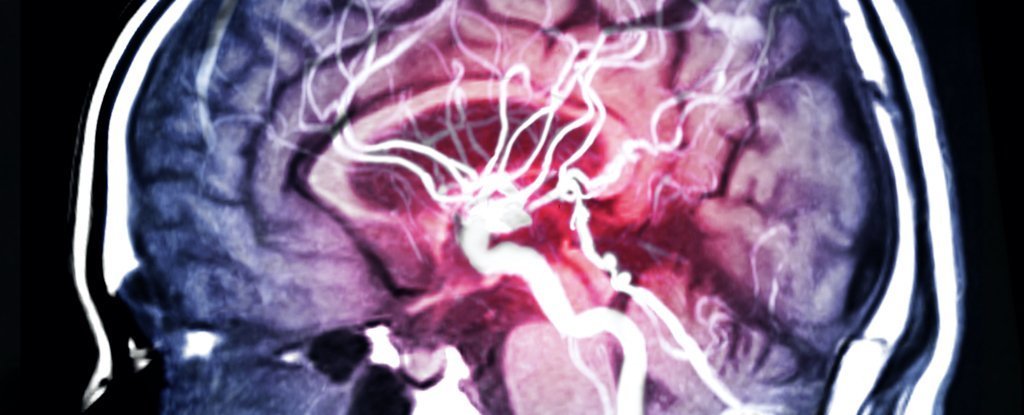

But Ely says he’s optimistic that COVID-related brain changes are reversible-one way or another. Some preliminary research also suggests blood-thinning drugs may help breakup tiny “ microclots” in the blood that are linked to systemic inflammation, potentially relieving Long COVID symptoms including fatigue, brain fog, and difficulty concentrating.Īs of now, there are no proven therapies for people with Long COVID symptoms, neurologic or otherwise. That approach is particularly exciting, Nath says, because it entails a therapy that is already used to treat a range of autoimmune and neurologic conditions-so if it proves effective, it could be rolled out to Long COVID patients relatively quickly. NINDS is currently enrolling patients for a study on immunotherapy as a potential treatment for neurologic Long COVID. That approach could be risky for people with Long COVID, many of whom experience worsened symptoms after mental or physical exertion, Ely says-but changing the immune system’s function in hopes of reducing inflammation in the brains of people with Long COVID is another promising route. Ely has found that “cognitive rehab,” a process of rebuilding the brain’s function through targeted mental exercises, can help people who develop similar cognitive decline after stays in the intensive-care unit. While there may not be a single solution, that doesn’t mean there’s no solution. “We’re not looking for a magic bullet that will solve all these problems” at once, he says. Damaging these support cells, Ely says, can kick off a domino effect that leads to tissue death in the brain.īut, Ely says, “almost certainly there are multiple processes going on”-it could be that the virus both directly affects the brain and causes changes to the immune system that lead to neurocognitive issues. Wes Ely, who researches brain disease at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, says he’s convinced SARS-CoV-2 can attack the “support cells” of the brain, or those ensure neurons are able to keep the brain and body functioning normally. There’s still a gap in knowledge there.”ĭr. “Some have found it, some have not, and some people who have found it, have found very small amounts. Researchers behind an April 2023 study not yet been peer-reviewed also found SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins-which are found on the virus’ surface and allow it to enter human cells-in the brains of people who died from COVID-19.īut the research is “inconsistent,” Nath says.

Covid brain fog depression full#

In one instance, he says, they found viral proteins-but not the full virus-in biopsied tissue from someone who had COVID-19 at the time they were undergoing brain surgery for epilepsy. His team has continued to study the brains of COVID-19 patients and has yet to find concrete evidence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in those organs.

To Nath, however, that’s still an open question, and one worthy of more research. In all but one of those individuals, the researchers found the virus’ genetic material in central-nervous-system tissue-which, they wrote, “prov definitively that SARS-CoV-2 is capable of infecting and replicating within the human brain.” Since Nath’s brain-scanning project early in the pandemic, other researchers have found the virus in the brains of people who died from COVID-19.įor a 2022 paper in Nature, researchers analyzed brain tissue of 11 people who had COVID-19 when they died.

Their findings pointed to the latter-but researchers still haven’t ruled out the possibility that the virus has direct effects on the brain. Going into that study, Jehi says, her team wanted to determine whether the SARS-CoV-2 virus was entering the brain and causing damage directly, or triggering an immune response that led to brain changes. “We found many areas of overlap between the two, and these areas of overlap centered on…inflammation in the brain and microscopic injuries to the blood vessels,” she says. And in a 2021 study, Jehi and her colleagues compared the brains of people with Long COVID and Alzheimer’s disease. She’s found evidence of abnormal inflammation in people with chronic post-COVID headaches. Lara Jehi, who researches COVID-19 and the brain at the Cleveland Clinic, also points to inflammation as a possible trigger for COVID-19’s neurologic symptoms. In people who survive COVID-19, brain inflammation may also explain years-long symptoms like brain fog and memory loss-though “we don’t know for sure,” Nath says.ĭr.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)